Michael Wood on the ongoing legacy of slavery

"Slavery’s effects are still working themselves out in our lives today," writes historian Michael Wood

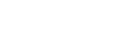

Sometimes an archaeological find can open a window onto the past so vivid, so immediate, that it comes like a flash of lightning.

This summer, a discovery was made at an archaeological dig in the small town of Abandze on the coast of Ghana, 70 miles west of Accra. The dig was inside the ruins of Fort Amsterdam, built by the Dutch in the 17th century on a hill above a beach fringed with coconut palms, where Atlantic rollers crash and painted fishing boats with long, curved prows bob in the surf. The fort was a brutalist rectangle with circular and square corner towers, and for more than 200 years it was used for the slave trade. But now, under its earth floor, traces have been uncovered of an earlier fort built by the British from 1638.

The first British entrepôt anywhere in Africa, it bore a famous name, Cormantin. At first it was used for trading gold, ivory and exotica, but then its commerce became people. In 1663, King Charles II granted a charter to the Company of Royal Adventurers (later the Royal African Company), giving it monopoly rights over the slave trade in which Britain would become a key mover. The exact site was long uncertain, but now here it was.

Under the earth were a wall, a brick drain, a gun flint, broken bits of 17th-century tobacco pipes, the spouts and necks of glazed tableware. Everyday fragments from one of history’s greatest crimes. The find took me back nearly 40 years. Back then, I was making a series that told a slavery story – pioneering in those days, when Britain’s role in emancipation was the thing that was stressed.

- Read more | A brief guide to the transatlantic slave trade

We were looking at a group of Afro-Caribbean families in Leicester who had come to the UK in the 1950s from the island of Barbuda, a desolate, almost waterless place north of Antigua. From the late 1600s till emancipation, and after, the island was owned by the Codrington family (who founded the All Souls College Library in Oxford, and built a grand country estate at Dodington Park in Gloucestershire). The tiny island was later part of the British Leeward Island Federation and eventually became independent in 1981. But in the 1950s, in the wake of the Windrush, many Barbudan families migrated to Leicester, which was the hometown of the English parish priest on Barbuda, a Father Milburn. They are still there today.

The thing that distinguishes the Barbudan story is the Codrington archive: the single most important archive on the history of slavery, and one of the most extraordinary in British history. In over 8,000 papers – letters, maps, deeds inventories, notebooks and surveys – are the records of the Barbudan people from 1668 to emancipation and after (the last document is from 1944).

More like this

In 1980, the Codrington family decided to sell the collection, which they did in an auction at Sotheby’s that December, to a private buyer with interests in the oil deposits off the island (why the British government didn’t bid is a moot point). But after negotiating with the buyer’s lawyers and getting clearance from HM Customs and Excise, I was able to film the archive in a bonded warehouse under the flight path at Heathrow. Looking back it was like the last scene in Raiders of the Lost Ark.

Just lifting the lid off one of the packing cases took us back to the 18th century. There were our families: Beazers, Punters, Charleses, Webbers and Teagues – the surnames shared by virtually everyone from the island today, taken from the names of the white overseers and indentured labourers. They were families whose solidarity over the generations bred a strong group identity much admired by outsiders. And there in the documents was the name of the place they had been taken from in Africa: Coromantee.

Now here in 2023 was the exact place: the little coastal town, the beach, the palm trees, the thunderous surf, and the fort on the hill – the last thing they saw before they sailed over the horizon into the horrors of the Middle Passage. Perhaps 12 million people faced such a fate in the slavery era, of whom as many as 2 million perished on the journey. And these things leave very long legacies.

Some people talk today as if slavery was a thing that happened in the past, but not so: its effects are still working themselves out in our lives today. The compensation payments to British landowners for the freeing of their slaves were only finally paid off in 2015. The past, as Faulkner said, is never dead. It’s not even past.

This column first appeared in the October 2023 issue of BBC History Magazine

Authors

Start the year with a subscription to BBC History Magazine - £5 for your first 5 issues!

As a print subscriber you also get FREE membership to HistoryExtra.com worth £34.99 + 50% London Art Fair 2024 Tickets